Arizona’s impressive biogeographic spectrum, from the piñon-juniper woodlands of the Colorado Plateau to the spectacular hot deserts of the Sonoran, Mojave, and Chihuahuan, makes for quite a fantastic lineup of native plants. Thrilling to explore their natural habitat, many of these natives do well in cultivation.

Boiling down the “top” native plants of the Grand Canyon State is no easy task – and, it goes without saying, a thoroughly subjective one – but I’ve tried here to pull together a representative roundup of 10 utterly awesome members of Arizona’s floral cast. From diminutive wildflowers to grand trees, let’s survey the botanical rock stars of this select Arizona native plants list, shall we?

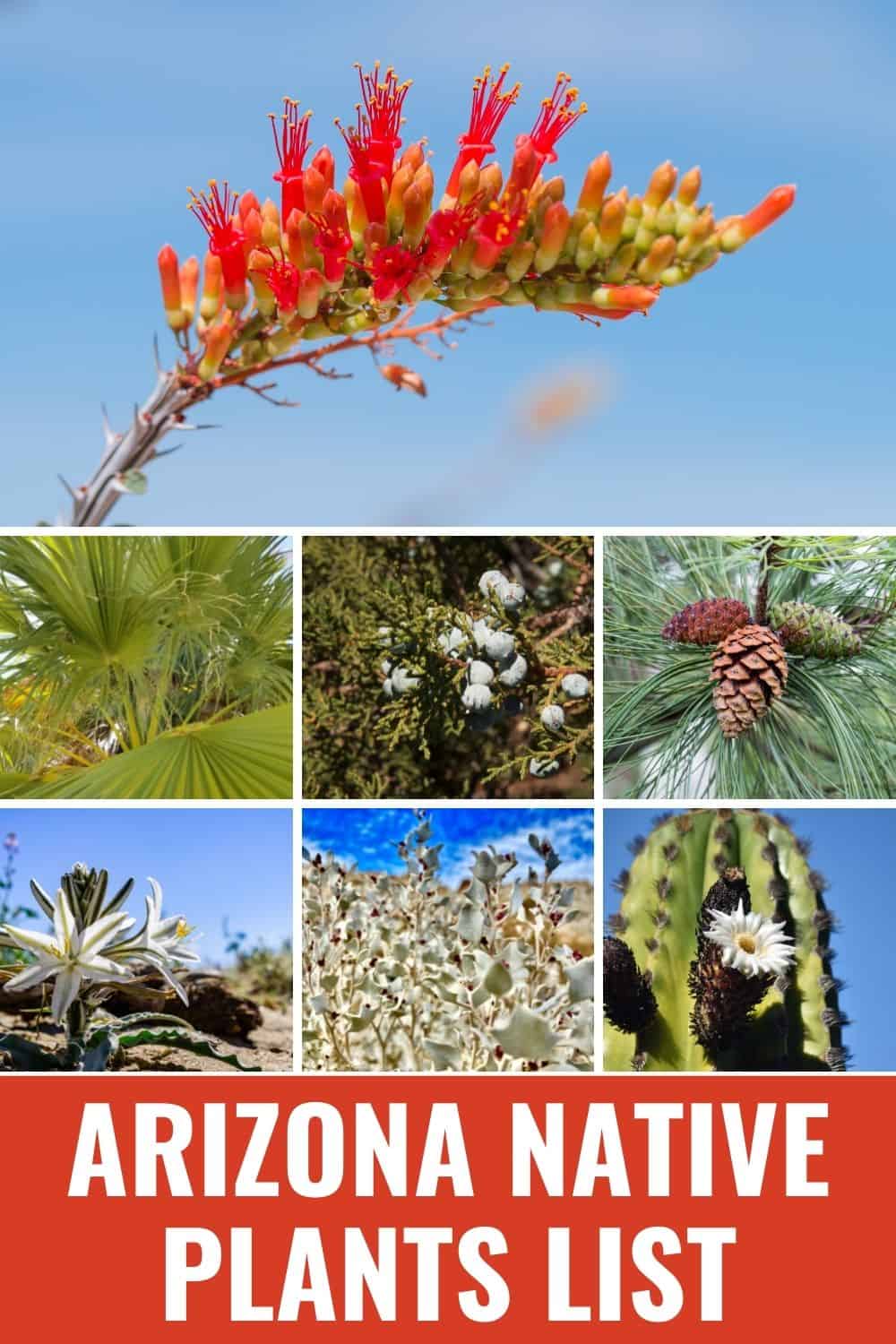

Arizona Native Plants List

1. Saguaro (Carnegiea gigantea)

There’s no more iconic Arizona plant, surely, than the mighty saguaro: the second-tallest of the world’s cacti after the Mexican cardón, and arguably the stateliest.

This titanic columnar cactus symbolizes the Sonoran Desert, though it’s not uniformly found there: it’s primarily a resident of the Sonoran’s Arizona Upland subdivision, which runs from southwestern Arizona east of the Colorado River south down to the vicinity of Altar in Sonora. Saguaros soaring to 40 feet or more in height above paloverde thickets form cactus “forests” on the region’s bajadas and foothill slopes. Backdropped by craggy purple mountains, these saguaro communities create for many around the world the iconic image of the American Southwest.

The saguaro is, unsurprisingly, enormously important from an ecological perspective: its fluted trunk providing nesting hollows for elf owls and woodpeckers, its nectar-feeding a host of different pollinators, and its fruit a vital food source – including for such native Sonoran Desert peoples as the Tohono O’odham.

Saguaros provide a spectacular addition to native xeric gardenscapes, requiring only a well-drained, sun-drenched spot to flourish. Occasionally maturing as a single column, they more typically branch upon reaching 10 or 15 feet in height. They sport their white blooms – Arizona’s state flower – in late spring. See a state flowers list here.

2. Desert Lily (Hesperocallis undulata)

A super-showy wildflower of harsh, sandy, or rocky Mojave and Sonoran flats, desert lily unfurls a big, white, flaring flower on the heels of rain: one of the cooler sights out there in the desert “wastes.”

The spring-blooming flower stands tall on a thick stalk above a bed of long, slender, ripple-edged, gray-green leaves, less immediately snazzy than the bloom but rather striking in their own right.

Also called the Ajo Lily, this lovely herb isn’t all that easy to cultivate, though some successfully grow it from seed in very dry, sandy soil. It usually takes a few years before the bulb will shoot up that knockout, trumpet-shaped flower.

3. Elephant Tree (Bursera microphylla)

The rare elephant tree, or tortore, is the far northern representative of a family of otherwise mostly tropical shrubs and small trees, reaching the extreme southwestern U.S. on rubbly Sonoran Desert slopes in Arizona and California.

Despite its limited distribution – it doesn’t endure frost well – the elephant tree ranks among Arizona’s most arresting native plants with its bulbous trunk of peeling bark. That swollen-looking trunk is a desert adaptation, serving as an efficient water-storing vessel.

This is a squat, bottom-heavy succulent occasionally reaching 15 feet or so but often much shorter; the small pinnately compound leaves resemble an acacia’s.

Its creamy flowers bust out in summer, and the fruits attract birds and other wildlife. Sometimes available from specialty nurseries, the elephant tree can thrive as a container planting and also in the ground on warm, sunny, frost-protected sites, where – no surprise – it requires little water once established.

4. Desert Holly (Atriplex hymenelytra)

This little shrub is one of the hardiest plants in the Mojave and Sonoran deserts, capable of withstanding some of the most withering conditions in alkaline flats and dry washes. Its contorted, creeping stem sends up dense tangles of branches cloaked in silvery, serrated, powdery leaves very much resembling true holly: quite the looker of a tough-as-nails subshrub.

Producing tiny flowers between January and April, the desert holly serves as a staple food for the desert bighorn sheep. In cultivated settings, it fares best in dry, well-drained soil with the bare minimum of water, forming a super-attractive, utterly low-maintenance desert groundcover.

5. Ponderosa Pine (Pinus ponderosa)

This most defining tree of the American West is also one of the world’s biggest pines, outsized only by the sugar pine with which it overlaps in the Southern Cascades, Klamath Mountains, and the Sierra Nevada; you could also make a solid argument that it’s the most all-around impressive, between its great stature and its fiery orange plated bark.

It’s widespread in northern and central Arizona and scattered in the sky-island ranges of the state’s southwest, where it rubs boughs with the very similar-looking Arizona pine. The Mogollon Rim edging the south end of the Colorado Plateau and cutting across much of Arizona’s middle supports what’s widely touted as the world’s largest continuous ponderosa forest. Visitors to the North Rim of the Grand Canyon, meanwhile, marvel at the vast ponderosa stands blanketing so much of the Kaibab Plateau.

Ponderosa pine holds such a huge range across western North America that it’s split into several major regional forms; Arizona supports the so-called Rocky Mountain ponderosa. This interior variety doesn’t reach quite the epic proportions of the Pacific or the Columbia ponderosas, but can still grow past 100 feet and show off a nice, stout “yellow-belly” trunk that exudes a vanilla or butterscotch scent. The long, three-bunched needles and hefty cones are other attractive features.

Outside of the hottest southern and lowland Arizona gardens, ponderosa can be a versatile, high-value addition to a larger property, and can also handle container-growing.

Best cultivated in sunny or part-shade spots, ponderosas tolerate a range of soils and are drought-tolerant as mature trees, though saplings need more water and older trees will appreciate occasional hearty drinks during long dry spells.

6. Ocotillo (Fouquieria splendens)

The ocotillo’s spray of whiplike stems draws the eye in its wide-open haunts across Arizona’s drylands, its native range in the Southwest anchored by the Sonoran and Chihuahuan deserts. Also called torchwood, the ocotillo is, like the elephant tree, the northernmost of its family, which consists of roughly a dozen mainly Mexican shrubs.

The ocotillo’s thorny, wild-looking stems, which may reach more than 20 feet tall, are often leafless, but after a rain, they erupt with small, dense leaves that wither and drop with the next dry stretch.

The most striking visual feature of the ocotillo, though – well, aside from its overall octopus-esque appearance – is its bloom: long, blazingly red-orange flowers often sported when the stems are otherwise naked. Hummingbird magnets, those flower clusters, which bloom between March and June, may reach a foot in length. The ocotillo needs full sun and only occasional water to put on its dazzling foliage and blossom displays in the Southwestern garden, where it’s often used as a hedge or screen.

7. Skyrocket (Ipomopsis aggregata)

The fact that this distinctive wildflower is so widespread in western North America doesn’t make it any less of a showstopper in the native garden – far from it.

Also called scarlet gilia, scarlet trumpet, or desert trumpet, skyrocket fires up rocky slopes and grassy woodlands and scrub of northern and central Arizona with its iconic tubular flowers, usually a spectacular fiery red but occasionally orange or pink as well. Those corollas, which put on their display between May and September, spangle tall stems that may reach nearly six feet tall, with the delicate, pinnately divided leaves denser toward the base of the plant.

Given its eye-catching beauty, it’s no surprise skyrocket is a popular component of many gardens. Preferring full sun, it can usually get by just fine on rainfall alone.

8. Alligator Juniper (Juniperus deppeana)

Arizona’s heftiest juniper, the alligator juniper is also the most distinctive. It gets its name – and some of its alternative labels, such as checkerbark juniper – from its thick, segmented bark, reminiscent of crocodilian hide.

Growing a rounded or pyramidal crown, alligator juniper is widespread in Arizona mostly south of the Mogollan Rim, growing as part of a variety of plant communities including pinon-juniper woodland, pine-oak forest, and Madrean evergreen woodland, and often overlapping with oneseed juniper. Native peoples in the Southwest coveted the wood of alligator juniper for building shelters and fences.

The hefty, gator-skin trunk and sculptured, evergreen canopy makes alligator juniper – drought and cold-tolerant, thriving in full sun on dry, well-drained sites – a handsome addition to landscaping. Besides offering all-around shelter for birds, its berrylike fruits appeal to critters as well; in the wild, everything from songbirds and wild turkeys to coyotes and deer snack on them.

9. Teddy Bear Cholla (Cylindropuntia bigelovii)

The “teddy bear” part of this cholla cactus’s name is kind of perverse: while it’s true that the plant’s arms or joints look rather furry, they’re actually packed with some of the densest, prickliest barbs of any Southwestern cactus. In other words, this is definitely a “look-but-don’t-touch” kind of teddy bear. It’s one of a number of species sometimes called a “jumping cholla,” given how readily those spiny joints break off with the slightest brushing against.

Some Sonoran Desert animals take direct advantage of the teddy bear’s spines: Cactus wrens nest within the natural fortress, and packrats guard their nests with cholla joints.

Sometimes growing more than six feet tall, teddy bear cholla is an extremely attractive plant despite its formidable armament, its golden spines almost giving it a glow in full sunlight. The greenish or yellowish flowers emerge at the end of those “fuzzy” joints between February and May.

Careful gardeners relish having such a Dr. Suess-style native in their yard; teddy bear cholla has minimal needs when placed in full sun on dry, well-drained soil, and besides its aesthetic value can form a natural barrier.

10. California Fan Palm (Washingtonia filifera)

The sole palm native to western North America – and, along with the royal palm of South Florida, the biggest indigenous U.S. species – the California fan palm or “desert palm” has been widely planted in the Southwest.

Wild palm groves, however, are found only in a highly scattered natural range in the Sonoran and Mojave deserts associated with canyon drainages and springs. The famous, dramatically situated California fan palms of the rugged Kofa Mountains are thought to be Arizona’s only truly native colony, a relic outpost occupying the steep and sheer-walled Palm Canyon.

This is certainly among the most impressive native trees in the country, growing up to 60 feet tall and typically sporting a shaggy mane of dead fronds under the lush green live leaf-blades. Those with large-enough properties to accommodate a California fan palm can site them in full sun and well-drained soil, with only periodic watering required – sometimes none, if precipitation’s decent enough. These desert palms are hardy down to 18 degrees F.

Native Plants Of Other States

Oregon Native Plants List: 14 Perfect Pacific Northwest Flowers

Tuesday 14th of February 2023

[…] Arizona native plants […]

Best Landscaping Ideas For Your Home

Sunday 29th of August 2021

[…] Arizona Native Plants List: 10 of the Grand Canyon State’s Most Remarkable Floral Representati… […]