Taking on DIY projects around your home and garden can be incredibly rewarding. From building a new planter box to installing outdoor lighting, the satisfaction of doing it yourself is hard to beat. When projects involve electricity, however, the stakes get much higher.

A small misstep can lead to big problems, including shock hazards, equipment damage, and even house fires. Understanding the most common electrical mistakes is the first step toward keeping your home and family safe. Let’s explore the errors many homeowners make and learn how to avoid them for a safer, more secure home, verified by home experts and electricians.

Warning: Always consult an electrician to avoid electrocution, fire hazards, and more.

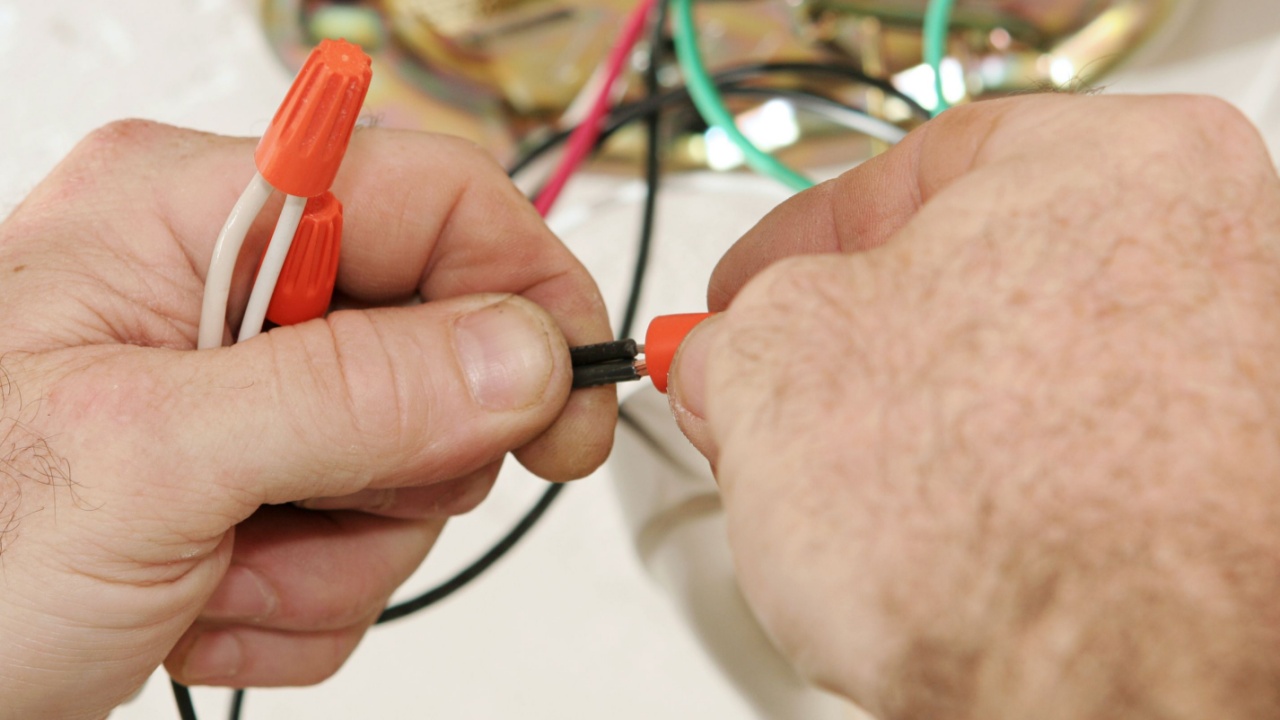

1. Cutting Wires Too Short

Image Credit: Shutterstock.

Trying to connect wires that are too short inside an electrical box is not just frustrating; it’s a serious safety risk. The National Electrical Code (NEC) requires at least six inches of free wire extending from the opening of the box. This length provides enough slack to make secure connections. When wires are too short, connections can become loose over time. Loose connections are a primary cause of arcing, an electrical discharge that generates intense heat and can easily start a fire.

If you open an outlet or switch and find the wires are barely long enough to reach the terminals, you have a problem. The best solution is to add “pigtails.” These are short pieces of new wire that you connect to the existing short wires, giving you the length you need to work safely. Use a push-in connector or a lever nut to make splicing the pigtails onto the stubby wires easier and more secure.

- The Problem: Wires are too short to make a secure connection, leading to loose connections and fire risk.

- The Rule: The NEC requires at least six inches of free wire.

- The Fix: Extend short wires by adding “pigtails” using secure connectors. (Consult an electrician.)

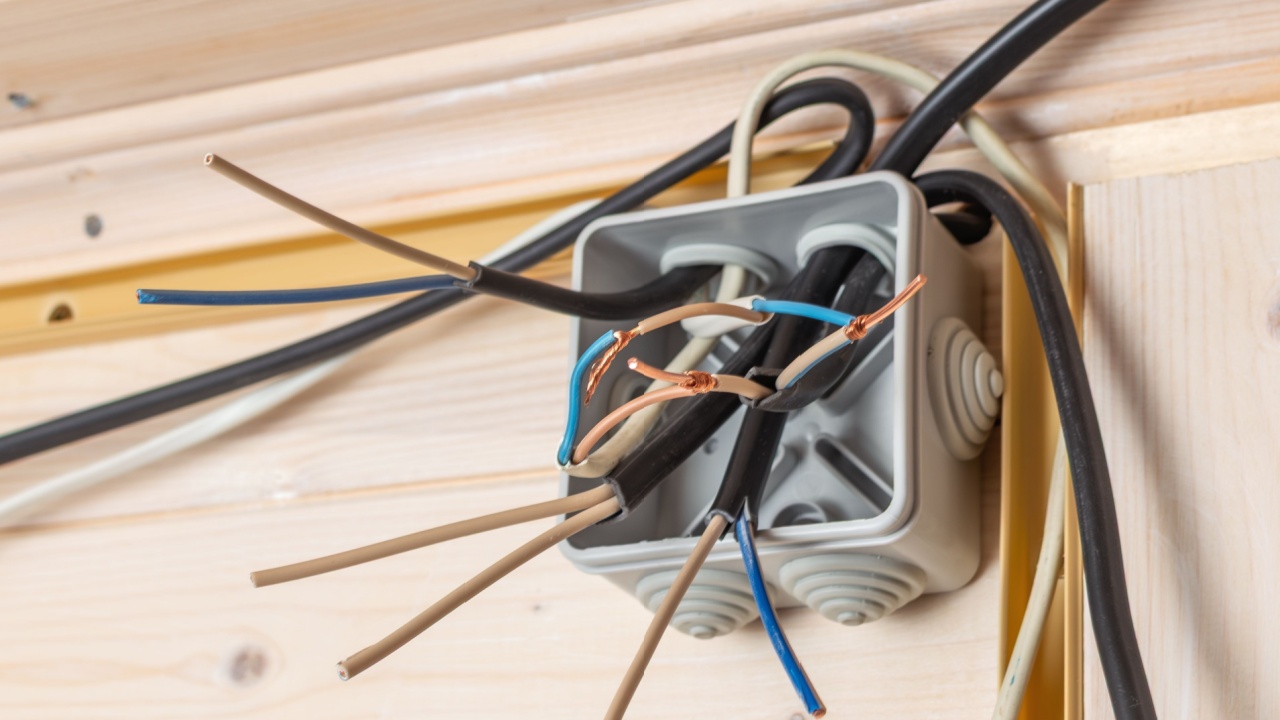

2. Making Connections Outside of an Electrical Box

Image Credit: Shutterstock.

Every electrical connection where wires are spliced together must be contained within a covered electrical box, often called a junction box. These boxes are designed to protect the connections from physical damage and to contain any sparks or heat if a connection fails. Wires simply twisted and taped together inside a wall or ceiling are a major fire hazard waiting to happen. The tape can degrade, and the connection can come loose, exposing live wires to flammable materials like wood framing or insulation.

If you discover connections made outside of a box during a renovation or repair, it’s crucial to fix this immediately. Turn off the power to the circuit, and install an appropriate electrical box. If you’re not near a wall stud, you can use a “remodel” or “old work” box, which has tabs that clamp onto the drywall. Safely remake the connections inside the new box and install a cover plate.

- The Problem: Unprotected wire splices are vulnerable to damage and can easily start fires.

- The Rule: All wire connections must be inside a covered electrical box.

- The Fix: Install a proper junction box and remake the connections inside it.

3. Not Using the Screw Terminals on Outlets and Switches

Image Credit: Shutterstock.

Many modern outlets and switches have small holes in the back for a method called “backstabbing,” where you simply push the straight end of the wire into make a connection. While this is technically allowed by code, it is not the most reliable method. The spring clips inside that hold the wire can weaken over time, leading to loose connections, overheating, and potential arcing.

Professional electricians almost always prefer using the screw terminals on the side of the device. This creates a much more secure and durable mechanical connection. To do this, strip about 3/4 of an inch of insulation from the wire, form a C-shaped hook in the copper, and loop it clockwise around the screw. As you tighten the screw, the clockwise hook ensures the wire is pulled tighter under the screw head, creating a solid connection that won’t easily come loose.

- The Problem: “Backstabbed” wire connections can become loose, creating a fire hazard.

- The Solution: Use the more secure screw terminals on the side of the device.

- The Method: Wrap the wire clockwise around the screw before tightening.

4. Reversing the Hot and Neutral Wires

Image Credit: Shutterstock.

This is a common and dangerous mistake. In a standard circuit, the black wire is “hot” (it carries the power), and the white wire is “neutral” (it completes the circuit). While a device like a lamp may still turn on if these are reversed, it creates a serious shock hazard. The metal socket of a light fixture, for example, is supposed to be connected to the neutral wire. If it’s accidentally connected to the hot wire, the entire socket becomes energized, and you could get a severe shock just by touching it while changing a bulb.

To avoid this, always pay attention to the terminals. The hot (black) wire connects to the brass or copper-colored screw. The neutral (white) wire connects to the silver-colored screw. The bare copper or green wire is the ground, and it connects to the green screw.

- The Problem: Reversing hot and neutral wires energizes parts of a fixture or appliance that shouldn’t be, creating a shock risk.

- The Rule: Black (hot) wire to the brass screw; white (neutral) wire to the silver screw.

- The Check: Use a receptacle tester to confirm your outlets are wired correctly.

5. Overfilling an Electrical Box

Image Credit: Shutterstock.

It might be tempting to stuff as many wires as possible into one junction box to keep things tidy, but this is a violation of the electrical code and a fire hazard. Wires generate a small amount of heat, and packing them too tightly prevents that heat from dissipating. Overheating can degrade the wire insulation, leading to shorts and fires.

The NEC has specific rules for “box fill,” which calculate how many wires, devices (like switches or outlets), and clamps can safely fit into a box of a given size. As a general rule, if you have to struggle to fit everything back into the box and get the cover on, it’s probably overfilled. The solution is simple: install a larger box.

- The Problem: Crowded boxes trap heat, which can damage wire insulation and cause a fire.

- The Rule: Follow NEC box fill calculations to determine the right box size.

- The Fix: If a box is too full, replace it with a larger one.

6. Installing Cables Without a Clamp in Metal Boxes

Image Credit: Shutterstock.

When running a cable into a metal electrical box, it must be secured with a cable clamp where it enters. Metal boxes have “knockouts” stamped circles that you punch out to run wires through. The edges of these holes are sharp and can easily chafe or cut through the plastic sheathing of the cable over time due to vibrations or movement. If the insulation is compromised, the live wires can come into contact with the metal box, energizing it and creating a severe shock or fire hazard.

Cable clamps are inexpensive and easy to install. They fit into the knockouts and provide a smooth, secure anchor point that protects the cable sheathing from the sharp metal edges. Don’t overtighten the clamp, as this can pinch and damage the wires inside.

- The Problem: Sharp edges of metal boxes can cut into cable sheathing, creating shock and fire risks.

- The Solution: Secure every cable entering a metal box with a proper cable clamp.

- The Tip: Ensure the clamp is firm but not so tight that it damages the wires.

7. Using the Wrong Size Wire for the Circuit

Image Credit: Shutterstock.

The size, or gauge, of an electrical wire determines how much current it can safely carry. Using a wire that is too small for the circuit’s amperage is a critical mistake. For example, a 20-amp circuit requires 12-gauge wire. If you use a thinner 14-gauge wire (which is only rated for 15 amps), the wire can overheat like a toaster element when a heavy load is plugged in, melting the insulation and potentially igniting surrounding materials.

When extending or adding to a circuit, always match the wire gauge to what’s already there and ensure it’s appropriate for the circuit breaker size. As a rule of thumb for household wiring, 15-amp circuits use 14-gauge wire, and 20-amp circuits use 12-gauge wire. Remember, it’s always safe to use a thicker wire (lower gauge number), but never a thinner one.

- The Problem: Undersized wires overheat, creating a serious fire hazard.

- The Rule: Match the wire gauge to the circuit’s amperage (14-gauge for 15 amps, 12-gauge for 20 amps).

- The Fix: If you’re unsure, check the existing wiring or consult an electrician. Never downsize the wire.

8. Incorrectly Replacing a Two-Slot Outlet

Image Credit: Depositphotos.com.

Older homes often have two-slot outlets that lack a third hole for the ground pin. A common mistake is to simply replace these with modern three-slot outlets. This is dangerous because it creates a false sense of security. The ground connection provides a safe path for electricity to travel in case of a fault. Without a ground wire connected, that path doesn’t exist, and the frame of an appliance could become electrified during a malfunction.

The safest NEC-approved solution is to replace the first outlet on the circuit with a Ground-Fault Circuit Interrupter (GFCI) outlet. A GFCI will still work without a ground wire and provides excellent shock protection. Be sure to use the included sticker that says “No Equipment Ground” on the face of the outlet. This informs users that while the outlet accepts three-prong plugs, the circuit is not grounded.

- The Problem: Replacing a two-slot outlet with a three-slot one without a ground wire offers no fault protection.

- The Solution: Install a GFCI outlet as the first receptacle on the circuit and label it “No Equipment Ground.”

- The Benefit: A GFCI provides personal shock protection even on an ungrounded circuit.

9. Recessing Electrical Boxes Behind Wall Surfaces

Image Credit: Shutterstock.

An electrical box must be mounted flush with the finished wall surface (or protrude slightly). When a box is sunk too deep into the wall, perhaps after adding a layer of paneling or a tile backsplash, a gap is left between the box and the cover plate. This exposes the surrounding combustible materials, like wood studs or drywall paper, to potential sparks or heat from inside the box. For noncombustible surfaces like tile, the box can be recessed up to 1/4 inch, but for flammable surfaces like wood paneling, it must be perfectly flush.

The fix for a recessed box is a simple and inexpensive device called a box extender. This plastic or metal ring fits inside the existing box, bringing the edge flush with the new wall surface. It safely bridges the gap and properly encloses the wiring.

- The Problem: A gap between the box and the wall exposes flammable materials to potential sparks.

- The Rule: Boxes must be flush with the finished wall surface.

- The Fix: Use a “box extender” to bring the edge of the box out to meet the wall surface.

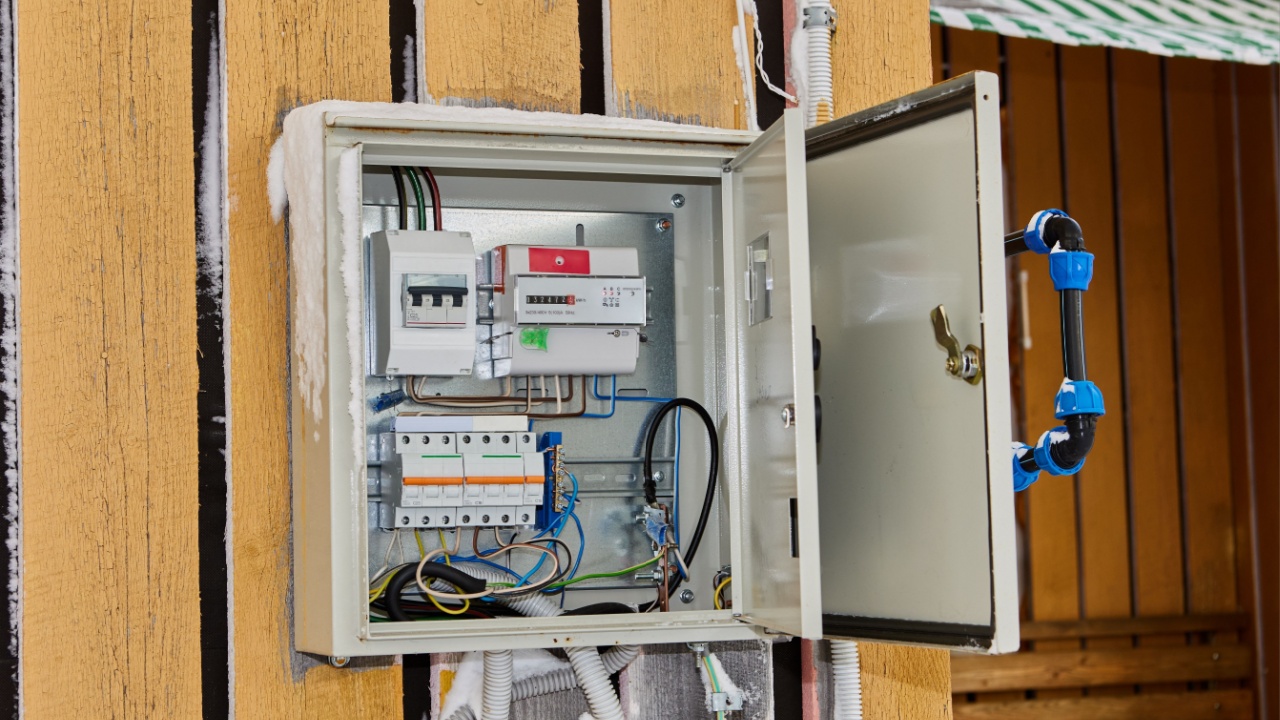

10. Overloading a Circuit

Image Credit: Shutterstock.

A constantly tripping circuit breaker is a clear warning sign. It means you are drawing more power than the circuit is designed to handle. Overloading a circuit can cause the wiring to overheat, which damages the insulation and creates a fire risk. Common culprits are high-draw appliances like space heaters, hair dryers, window air conditioners, and microwaves, especially when run on the same circuit.

To solve this, you need to manage your electrical load. Calculate the total wattage of the devices on a single circuit (watts = volts x amps; a 15-amp circuit can handle 1,800 watts). Try to move high-power appliances to different circuits. For things like a new microwave or window AC unit, the best practice is to run a new, dedicated circuit directly from the electrical panel.

- The Problem: Drawing too much power trips breakers and can cause wires to overheat.

- The Solution: Distribute high-wattage appliances across different circuits.

- The Best Practice: Run a dedicated circuit for new, power-hungry appliances.

11. Using the Wrong Box for a Ceiling Fan

Image Credit: Shutterstock.

A ceiling fan is heavy and, more importantly, it moves. The vibrations and torque it generates can easily pull a standard electrical box out of the ceiling. A standard plastic or metal box, designed to hold a lightweight light fixture, is not strong enough to support the dynamic load of a fan. If the box fails, the fan can come crashing down.

When installing a ceiling fan, you must use a box that is specifically rated for fan support. These boxes are typically made of metal and are designed to be mounted directly to a ceiling joist or a special brace installed between joists. The box will be marked “Acceptable for Fan Support” and will state the maximum weight it can hold.

- The Problem: A standard light fixture box cannot support the weight and movement of a ceiling fan.

- The Solution: Use only a ceiling box that is specifically listed and rated for fan support.

- The Check: The box must be clearly marked as fan-rated.

12. Misusing a Voltage Tester

Image Credit: Shutterstock.

A non-contact voltage tester is an essential safety tool for any DIYer. It beeps or lights up when it detects voltage, letting you know if a wire is live. However, they are only effective if used correctly. The biggest mistake is assuming a circuit is dead after testing it once. The tester’s batteries could be dead, or it might not be sensitive enough to pick up a faint current.

The correct procedure is “Test, Use, Verify.” First, test your tester on a known live source, like a working outlet, to confirm it’s functioning. Next, turn off the breaker and use the tester to verify that the circuit you’re working on is dead. Finally, take the tester back to the known live source one more time to ensure it didn’t fail during your work. This three-step process confirms your tool is working and your circuit is truly off.

- The Problem: Relying on a tester that may have dead batteries or be malfunctioning.

- The Procedure: Test your tool on a live circuit, use it on your target circuit, and then verify it on the live circuit again.

- The Golden Rule: Always treat every wire as if it is live until you have proven it is dead.

13. Installing Too Many Protection Devices

Image Credit: Shutterstock.

GFCI (ground-fault) and AFCI (arc-fault) outlets provide critical protection from shock and fire, respectively. But you don’t need to install one of these expensive devices at every single outlet. A single GFCI or AFCI receptacle can protect all the other standard outlets “downstream” on the same circuit.

These devices have two sets of terminals: LINE and LOAD. The incoming power from the breaker panel connects to the LINE terminals. The wires that continue on to the rest of the outlets connect to the LOAD terminals. When wired this way, the device’s protective features are extended to all the downstream outlets, saving you money while ensuring complete safety for the entire circuit.

- The Problem: Wasting money by installing unnecessary GFCI/AFCI outlets.

- The Solution: Install one GFCI/AFCI at the beginning of the circuit and wire the other outlets to its LOAD terminals.

- The Benefit: Protects an entire circuit with a single device.

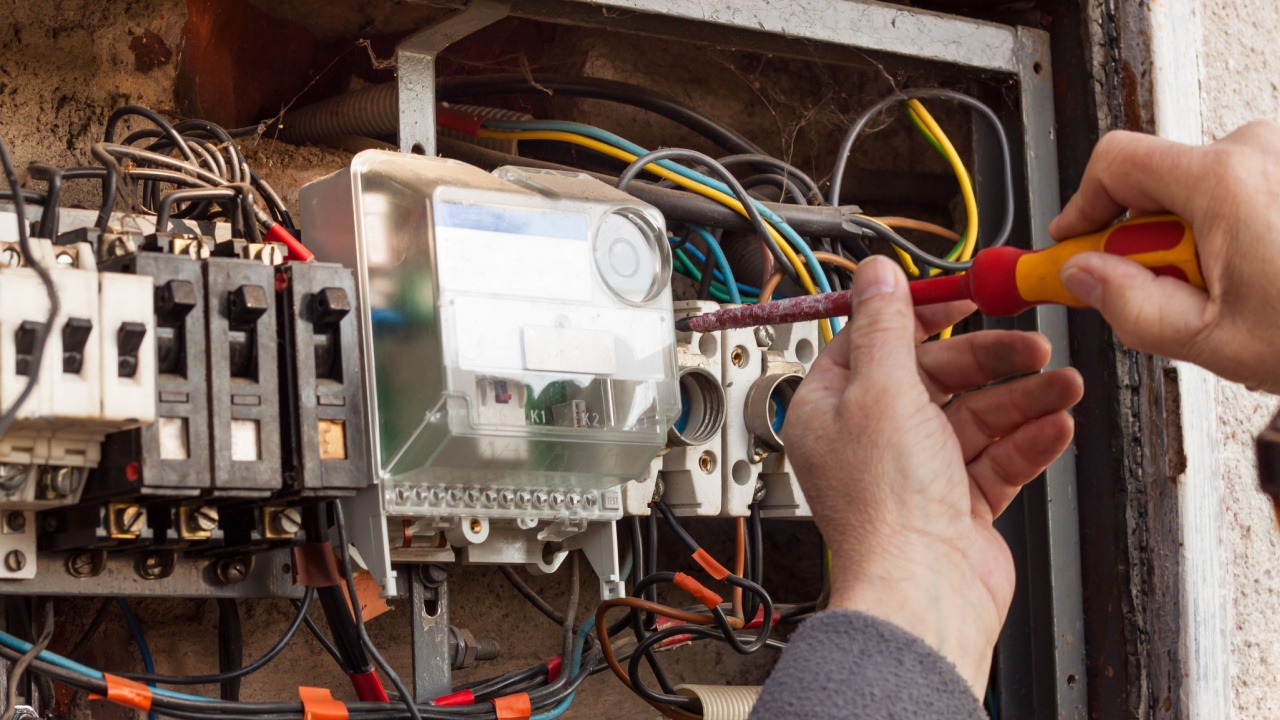

14. Getting in Over Your Head

Image Credit: Shutterstock.

While many DIY electrical projects are manageable, some tasks are best left to a professional. The most significant mistake a homeowner can make is continuing a project when they feel unsure, confused, or uncomfortable. Electrical work is unforgiving; one wrong move can have severe consequences.

Signs of trouble that almost always warrant a call to a licensed electrician include frequently tripping breakers that you can’t explain, flickering or dimming lights, a burning smell near outlets or switches, scorch marks on receptacles, or buzzing sounds from your electrical panel. Any work involving the main service panel, like upsizing a breaker, should also be handled by a pro.

- The Problem: Taking on complex or confusing electrical work without the proper knowledge.

- The Solution: Know your limits. When in doubt, stop work and call a licensed electrician.

- The Red Flags: Burning smells, buzzing sounds, and frequently tripping breakers require professional attention.

Managing a Safer Home

Image Credit: Shutterstock.

Avoiding these mistakes is a huge step toward ensuring your home’s electrical system is safe and reliable.

To be proactive, consider scheduling a professional electrical inspection every few years, especially if you live in an older home. An electrician can spot hidden issues before they become serious dangers. Take the time to learn the basics of your home’s electrical system, like how to shut off the main power and which breakers control which circuits.

By respecting the power of electricity and knowing when to ask for help, you can confidently and safely manage your home and garden projects for years to come.